Part One of my Summer 2010 trip

Links to all parts of this travelogue:

Part 1: Riga, Sigulda and Turaida

Part 2: Tbilisi, Mtskheta and Kazbegi

Part 3: Tbilisi, Gori and Uplistsikhe

Part 5: Doğubeyazit, Van and Diyarbakır

Part 1: Riga, Sigulda and Turaida

24th July, 2010 – Riga , Latvia

Centuries ago, whenever a man was about to set off on a journey, great currency was given to omens and portents. Lucky ones meant that the trip would be a successful one; an ill one spelt disaster or, if possible, cancelling or delaying the expedition.

It is a good thing that such things are not given great credence in 21st century Britain though, for if they were then I would never have set off for Riga

“I won’t be coming with you buddy, I’m sorry. I snapped my Achilles whilst playing football with school. I’ve been lain on the sofa all week; I can’t even climb the stairs let alone journey across half the Near East .”

So yes, it was with a heavy despondent heart and a worried head that I boarded Ryanair flight FR1664 to Riga, thoughts not on Asian adventures but instead expenditure, loneliness, marital woes and my two-year old son who I knew I’d be missing like hell.

But the plane did not start. The time for take off came and went but nothing happened. Everyone craned their heads to the back of the fuselage where there was an almighty commotion. A voice came over the tannoy: “Do we have a doctor on board?” Someone had collapsed; medical staff had to be called. Yes indeed, someone was definitely trying to tell me something.

Problem was, I never listen. And if you don’t believe me, ask my (ex) wife. She was always complaining about that very thing.

Back in the USSR Old City reminiscent of Prague or Bratislava

The hotel was situated in a fine art nouveau building itself and exceeded my expectations of what one should get for 20 lat per night (c. £28). The receptionist was friendly so I decided to see if she could help me out a little. My walk across town had revealed to me that Riga is far too spread out a place to see on foot, particularly in blistering summer temperatures, but on the way I had also come across a solution to this problem; a scheme whereby one could hire a bicycle for a lat per hour, (and a proper bicycle at that, sit up and beg with a big basket on the front!). The only snag was that you needed to call the company to do it and I had no phone. But within m inutes, with the aid of my receptionist, it was soon all arranged and out I went again to unlock my ‘Baltic Bike’.[1]

I cycled back to the Old City over the Akmens Bridge

By now I was hot and tired, but I forced myself round one more sight, the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia 1940-89. The name alone betrays how most Latvians view their five decades as a member republic of the USSR

I retired for tea in a pleasant café in the Old City

25th July, 2010 – Sigulda , Latvia

Experience has taught me that capital cities, no matter how beautiful or interesting, rarely give one a taste of the true flavour of a country. For that one must go to the provinces and so it was that on the second and last day of my short Latvian interlude, I decided to head out into the sticks.

Research on the net and in guidebooks had revealed two possible destinations for the day: Sigulda (‘The Switzerland of Latvia’) and Cēsis (‘The most Latvian town in Latvia

So Sigulda it was. I was footsore and tired however, even before I got on the train. It was another hot day and I walked over a mile from my hotel to the railway station, investigating the Freedom Monument and Riga’s Central Market en route, (I‘d long wanted to see the latter as it is housed in old zeppelin hangars acquired from the Germans after World War I).

The train was a grumbling Soviet Era DMU that made its way slowly out of the capital towards Sigulda, stopping every few minutes at halts in the middle of nowhere and never exceeding about 40mph. The journey was a fascinating one; coming out of Riga the train passed by huge Soviet industrial complexes now dormant and vandalised and sprawling housing projects. Prior to that journey, Riga

The city ended abruptly and then it was forest, endless flat forest, deciduous and coniferous, with the ramrod-straight railway line cutting through it like a knife. I was amazed that here, one of the most densely-populated and developed republics of the old Soviet Union , was so empty. Occasionally we’d stop at a halt with a few scattered houses around an unmade road and then the trees closed in again. Yes indeed, this was not Mitteleurope, this was Russia

As we trundled through the seemingly endless forest, I recalled a film that I’d watched about a year or so previously entitled Defiance which told the story of a group of Jewish partisans who hid out in the forests of nearby Belarus, built a community and held out for over two years against the Nazis. Although it was a true story, I struggled to understand when watching it how a military machine as organised and methodical as the German Army could fail to flush out such a band of rebels, but riding through that forest, I understood only to well. Forests such as that are indescribably big and must have been almost impossible to police. It would have taken a force of thousands to flush out the partisans and I began to understand just how the group portrayed in Defiance and countless others managed to cause such chaos for the German troops occupying the USSR

One settlement that looked particularly interesting was a place called Inčukalns. It had a station, a railway yard and a factory around which the people lived in workers’ housing units. As we passed I thought of how it reminded me of Revivim, the kibbutz I worked on in the Negev Desert

When I arrived in Sigulda it was stiflingly hot; a slight disappointment as I’d hoped that the ‘Switzerland of Latvia’ would be a little cooler than the capital, although that was always perhaps more hope than reality. After all, how Alpine can a place be in a country where the highest peak is a mere 311m?

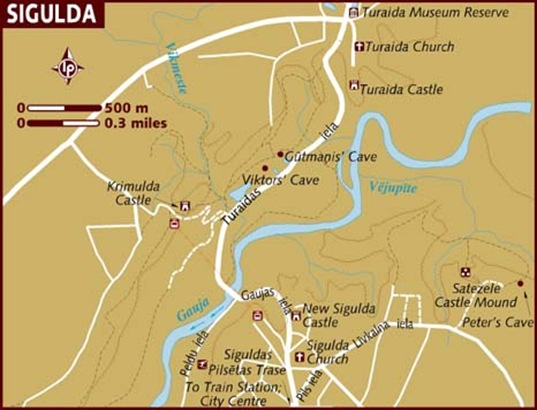

I’d decided to follow a walking route of around 6km outlined in my guidebook that linked the three castles in the district – Sigulda, Krimulda and Turaida – as well as a famous cave, a couple of stately homes and an open-air museum. It was easy-going and pleasant although I would have preferred a little less heat and sun on my head. Sigulda Castle, a picturesque ruin built by the atmospherically-named Brethren of the Sword, stood behind the new castle, a 19th century Gothic pile with beautiful gardens that I can imagine politiburo members once retiring to. After investigating both and the charming Lutherean church by the village pond, there was a cable car ride over the Gauja Valley

The mediaeval castle at Krimulda, this time built by the Archbishop of Riga who was the temporal as well as the spiritual leader of those parts back in the Middle Ages, was much destroyed and there was little of interest to see, but beside it was another 19th century stately home, now in use as a sanatorium. Wandering around the crumbling estate buildings and overgrown gardens, I was reminded of all those great 19th century Russian novels whose heroes and heroines shared their time between their St. Petersburg houses and their country estates where serfs doffed their caps and waited on them hand and foot. It was on an estate much like that at Krimulda that Yevgeny Onegin met Tatyana Larin, Yevgeny Bazarov ranted about nilhism and Konstantin Levin retired to work on the land and escape from the mindlessness of city life.

After Krimulda there was a steep descent through the forest and then a walk by wetlands, (on a path built by Latvian volunteers and Peace Corps members soon after independence), to the Gutmanis Cave, the largest in the Baltic States and home to the legend of Maija, the Rose of Turaida, a young maiden who killed herself rather than lose her purity to a Polish nobleman who wanted her for his wife. For the traveller however, the main attraction is the graffiti, some of it centuries old, which covers the entire surface of the cave. That and the water, once thought to be holy and still very refreshing on a hot summer’s day.

Refreshing cave water not withstanding, by this time I was tired, footsore and hot, and the final part of the trek was a stiff climb up the valley side to Turaida. As hills go it was no great shakes I suppose, but in my state it was truly the Hill of Hell and by the time I eventually conquered it I was streaming with sweat and ready for the train home.

At the top though was a restaurant, a Soviet Era canteen in a 1960s concrete block with faded linoleum table covers and a selection of proletarian staples served by an unsmiling matron of uncertain years. A lot of people would have sniffed at such an establishment, but to me it was a piece of history for such canteens are few and far between these days and they get less in number, (or even worse, they get renovated!), every year. To top it off, this place even had a small exhibition on the history of communal dining in the Soviet Union which I perused with relish. According to the exhibition, during Soviet times when there were often shortages in the shops, the same was not true in restaurants and so many people dined out just because they couldn’t get some of the foods that they wanted otherwise!

Having restored a little of my strength, I paid to enter the Turaidas Muzejrezervāts, an open-air museum that also included Turaida Castle Stockholm or the Blists Hill Museum

In Riga I made a detour to view the Academy of Sciences , a Stalinist wedding cake monolith akin to the Seven Sisters in Moscow and essential viewing on any Red Tourist’s Riga

Well, the best place in town when it is open that is, but it was a Sunday that day and obviously masseurs take the Sabbath seriously in Latvia as it was well and truly shut, so I left unwashed with a couple of hours to kill before I was due at the airport so I decided to walk to the hotel. After all, it didn’t look that far on the map…

I dined at a canteen half-way to my hotel and then walked on, the receptionist kindly letting me take a shower for free before catching my transportation on to the airport, a Baltic Air minibus that turned out to be a taxi with a chatty driver named Janis who cheerily discoursed on learning English, work and family before I left him outside the terminal and ended my first taster of the Baltics.

But what did I make of Latvia

One strange thing that I noticed was the amount of people, who spoke English to one another in Latvia

Anyhow, that was Latvia Soviet Republic Georgia

Next part: Tbilisi, Mtskheta and Kazbegi

[1] Owned by the same company that I later flew to Tbilisi Latvia

[2] Except for the Philippines

The construction of this Turauda Castle took three centuries starting from 13th century and ending in 16th century.For More Photos: http://www.worldfortravel.com/2014/04/20/turaida-castle-lativia-europe/

ReplyDeleteAli, nice photos. One of them looks familiar... I am happy for you to use it but can you post a link back to here please?

Delete