Greetings!

This week’s offering details what was arguably the best day trip of my life. Everyone has heard of Chernobyl, everyone knows what it symbolises. Of course why one should think of going there for an outing is less clear but hey, where else on earth do you go equipped with a Geiger counter rather than a sat nav and where else on earth can you find a whole city abandoned in a few hours, just left to rot as the vegetation takes over?

And where else on earth, a quarter of a century later, does the danger which destroyed that place still lurk, silent, unheard and unseen, yet real, an awesome menace that can bring you to your death, lurking in the trees, grass, water and moss..?

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue:

Ukraine

Moldova and Transdniestra

Romania

3.4: The Painted Monasteries of Bucovina

3.5: Targu Neamt, Agapia and Sihla

3.7: The Mocanita and Viseu de Sus

3.8: Viseu de Sus to Bucharest

Excursion: Chernobyl and Pripyat

The day after my little trip to Konotop, I was heading out of Kiev again, this time to a rather more famous – or infamous – destination. Several years ago I’d been reading an old issue of National Geographic at work when I stumbled across a photo essay on the city of Pripyat some one hundred kilometres to the north of Kiev right on the Belorussian border. Pripyat is a fairly new city, constructed from scratch in 1979 as a Soviet atomgrad – a series of new towns built to house the workers in nearby nuclear power plants. The moment that I saw the images I was desperate to visit for Pripyat is a unique city, unlike no other on earth for on the 27th April, 1986 its entire population of almost fifty thousand was evacuated in a single night and ever since then nature has been left to take over. The Soviets evacuated this brand-new flagship atomgrad because a day earlier there had been an accident at Reactor No. 4 of the nearby power station where most of Pripyat’s population were employed. That power station was called Chernobyl.

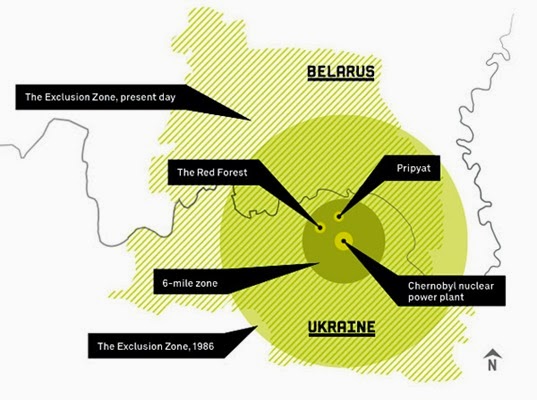

Since that date the whole region around Chernobyl has been sealed off to the world due to fatally high radiation levels. There are two zones of exclusion – the 30km and the 10km – and whilst within the 30km zone a few people now live – specialists working at the plant or elderly residents who have returned to their homes despite the risks – within the 10km zone in which both Pripyat and the power station itself are situated, no one dwells. However, since 2005 it has been possible to go on guided day trips into both and as soon as I knew I was travelling to Ukraine, then I knew that I just had to see Pripyat.

But I almost didn’t manage it. Tours are expensive – at just under £100 it was by far the priciest day trip that I’ve ever been on – but more than that, there’s the red tape. Bookings have to be made a week in advance in order to process all the bureaucracy and I was booked onto a trip with one operator when, only a few days before my departure for Kiev, he cancelled.

What was I to do? I was only in Kiev for a short while and I did so want to see Pripyat yet I was now past the five days cut-off point. I frantically emailed several other operators and some time later received a phone call from Canada of all places saying that one of them could squeeze me in. I booked up immediately and that is how I found myself standing in front of a hotel in the Podil district of the city with my fellow day-trippers, all waiting for a minibus to take us to the most infamous power station on earth.

There were six tourists and the driver who didn’t speak a word of English. Apart from me and the driver, all the other radiation-seekers were Americans: a pair of beardy university students and a family of three from Michigan, mom, dad and their tousle-haired son, soon to join the undergraduate ranks of his two bearded compatriots. Thus all introduced and crammed into the minibus, we set off through the dreary suburbs and then out into the wide, flat landscape that I’d seen so much of the previous day.

What we were headed for and had paid so much to enter were the Chernobyl Exclusion Zones, named the 10km and 30km respectively, (although the distances are approximate as neither are circular and both drift heavily to the west of the power station, that being the direction in which the winds blew most of the radioactive dust). When we got to the edge of the 30km zone it was like reaching the borders of a new country with a manned military checkpoint, a gate blocking the road and a high fence stretching off across the fields in either direction. Far more appealing to behold however, (although probably just as lethal to any unsuspecting young gentlemen), was our guide who joined us there and checked all our paperwork whilst Michigan kid and I winked at each other, looking forward to the rest of the day. Her name, she said, was Natalie, although I suspected that it was probably Natalya really, the anglicising being part of a process which she had energetically thrown herself into after spending a year in New York where she’d acquired a grating accent that was far less sexy than those of most of her English-speaking Ukrainian sisters. But there was method in her madness you see, for she was due to emigrate to Toronto in a year’s time, something which she was most excited about, as too were the Michigans who enthused over her future home and bade her cross the border sometime and come to their house to stay for a night or two. Whilst I too would have no hesitation in bedding her – if that is the correct term to use – I could not share her excitement about being Canada-bound. After all, why would anyone wish to swap a life in the former USSR where they’re about to host the European Football Championships and you get to work in a radioactive ghost city each day and eat borsch in the evenings, for a miserable existence in a country without any significant nuclear disasters or other history, and which considers ice hockey to be the pinnacle of sporting bliss. Indeed, mad, quite mad, although my vast life experience has taught me that women, particularly young and pretty ones, often are.

After the ‘border’ the road was empty, straight and forested on either side. It looked much like any of the other Ukrainian roads that we’d travelled along until we stopped by the large sign that had been erected in Soviet times to welcome people into the town ahead. The name on that sign was infamous the world over: Chernobyl.

Welcome to Chernobyl! (It’s buzzing!)

Welcome to Chernobyl! (It’s buzzing!)

The city of Chernobyl was not what I’d expected. It’s no dilapidated, overgrown ghost town but instead a reasonably – in comparison with many other Ukrainian cities – well-maintained living settlement where some former residents who have decided to return and the workers on the new sarcophagus for the radioactive reactor live for periods at a time. We drove through its empty streets to a small building that serves as a motel for the said workers and an information centre for us tourists, and after being ushered inside by the delectable Natalie, were treated to a display of photos and maps and a presentation on what exactly happened on that fateful day in 1986 and then over the weeks that followed.

On the 26th April No. 4 Reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station was shut down for routine maintenance and it was decided to test the electrical system to see if it could keep the reactor’s cooling system going in the event of power loss. However, something then went wrong and it could not and as the emergency cooling system had been switched off, the reactor began to overheat resulting in a nuclear explosion which killed two workers outright and shot nine tonnes of radioactive waste a mile up into the air.

The inhabitants of Pripyat, the town next to the plant, watched all of this in shock and disbelief from their apartments as firemen were sent in to try and quench the fires and in doing so received lethal doses of radiation. The blaze in fact continued for an entire fortnight and in total thirty-one firemen lost their lives in this initial struggle, although without their brave sacrifice, the death toll would have been much higher.

What made Chernobyl a double tragedy though, was the official response to the disaster. Partially due to ignorance over how to deal with such an incident, but far more motivated by a paranoid desire to keep things quiet, Pripyat – which lies less than a mile from the plant that it was built to serve – and the city of Chernobyl – which is a little further away – were only evacuated two days after the explosion, by which time thousands had been needlessly exposed to dangerous levels of radiation. The world at large however, including the population of the Ukrainian and Belarussian SSRs, only found out that there had been a major accident almost a week later when Swedish scientists discovered a rather large and unexplained radioactive cloud blowing north towards their territory. By this time considerable environmental damage had been inflicted not only on the area around Chernobyl but in surrounding countries as well, particular what is now Belarus and Poland.

Getting back into the minibus we continued on our way and at the edge of the city stopped at a modern monument dedicated to the firemen who lost their lives and a collection of vehicles that had been used to help combat the blaze.[1] Some of these looked like standard emergency or military hardware but others were a lot weirder, more like moon buggies than emergency service vehicles, but if we thought they were freaky, things were only just getting warmed up…

Chernobyl: Fireman Sam meets the Transformers…

Chernobyl: Fireman Sam meets the Transformers…

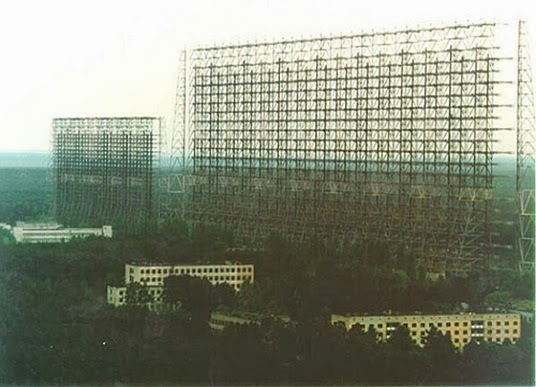

Outside the city we turned off down a small lane which ran for some distance through fields and then into the forest. There we stopped, got out and walked through the trees to get a view of our next ‘tourist site’. It was an old Soviet radar station, top secret back in the Cold War days, tuned into the airwaves of the decadent West. It’s technical name was the Duga-3 over-the-horizon radar station and it served as one of the Soviet Union’s state-of-the-art anti-ballistic missile warning stations. Unfortunately, we couldn’t go right up to the thing, (because of radiation levels, yeah right…), but still, it all felt very James Bond.

Ground control to Major Tom… (not my picture by the way)

Ground control to Major Tom… (not my picture by the way)

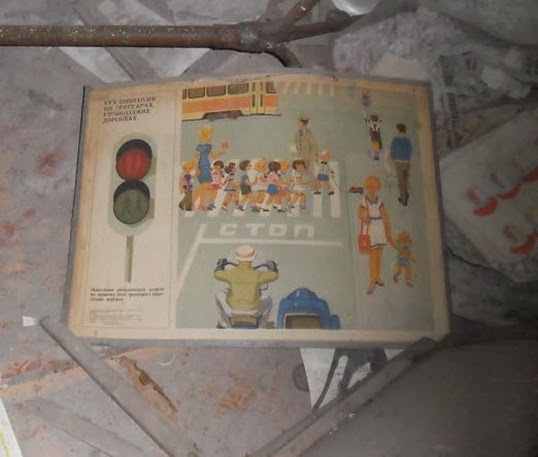

Our next stop though, was weirder still. In fact, it was plain disturbing. A small building, derelict, windows smashed as if everyone had suddenly just upped and left. Which of course, they had. There were desks, decaying toys, a room full of wire bunks, one with a freaky-looking doll which I suspect had been placed there purely to petrify passing Michigan moms, (it worked). The local kindergarten. A world of childhood, carefree and simple, abandoned. I picked up a mildewed and faded old textbook instructing good Soviet toddlers how to cross the busy road safely and shuddered. Ours was the only car left on the road now. The question remains, how many of those toddlers are still with us…?

After the hors d’oeuvres it was onto the main ‘attraction’ itself, the power station that caused all the trouble. First into view came the concrete-lined river, then the almighty cooling tower. After that, Reactors 5 and 6 which were still under construction when the accident occurred and so never completed. Then came the ones that did function: 1, 2, 3 and 4. We stopped by the roadside to have a look at them and at the worksite of the French company that is building a new sarcophagus which will replace the crumbling one hastily erected over Reactor No. 4 back in 1986 to contain the radiation. Natalie informed us that the workers on the project could only be at the site for twenty minutes at a time, after that they had the whole day off. To me that sounded like the kind of job I might excel at and I wondered where to apply.[2] Similarly, Natalie herself would work fifteen days on and then return home to Vinnitsa, several hundred kilometres south of Kiev for a mandatory fifteen days off. Again I wondered why she wanted to leave for what would undoubtedly be a much harder – and less interesting – existence in the suburbs of Toronto. True, money is a big incentive, but a job that gives you fifteen day holidays every couple of weeks?! Women, who can ever understand them?

Beauty and the Beast: Natalie by the Chernobyl cooling tower

Beauty and the Beast: Natalie by the Chernobyl cooling tower

Equally incomprehensible was the fate of the reactors. Nos. 1 and 2 were shut down immediately after the accident whilst No. 4 of course, was totally unusable. No. 3 however, which is physically attached to No. 4, only a thick concrete wall separating the two, stayed operation until 2005 when it was finally decommissioned! Imagine that; going to work every day in an ageing nuclear power station with only a few feet of concrete separating you from the decomposing site of the worst nuclear disaster in history! Jesus! In that position even I’d be tempted to swap it all for a life of drudgery in the freezing wilds of Toronto!

Particularly if Natalie was there to keep you warm at night…

Reactors Nos. 3 and 4. To the left of the chimney = blew up; to the right = worked until 2005

Reactors Nos. 3 and 4. To the left of the chimney = blew up; to the right = worked until 2005

The highlight of the tour however, was what came next: a walk around the ghost city of Pripyat. This is what I had come to see, what had really fired my imagination; the chance to visit a chunk of the old USSR untouched since the Gorbachev Era.

Mind you, Pripyat, even when it was inhabited, was never a standard Soviet city. As I’ve already said, it was newer than most other cities, only being established in 1970 and granted city status in 1979. Its population at the time of the explosion was 49,000, (the eventual projected population was to be around 70,000), most of whom were in some way or another connected to the huge and expanding power station next door. Pripyat was, after all, an atomgrad, one of a series of new cities planned and built specifically to service the USSR’s new nuclear power stations. And in atomgrads residents had more privileges, more services and access to more goods than in ‘normal’ towns and cities. This was not a socialist city, it was a model socialist city, a veritable beacon of progress for the proletariat.

That was then, but it clearly is not now. Almost two days after the explosion, when most of the residents had already been exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation, the entire city was evacuated by bus in two hours flat, moved to a new city, Slavutych, some thirty miles to the east. Since then Pripyat has been left untouched and nature has reclaimed her own to a degree that I found astonishing. I’d expected to be walking around an empty, ruined city with weeds and trees everywhere, instead we strolled through a forest with abandoned tower blocks peeping through the trees.

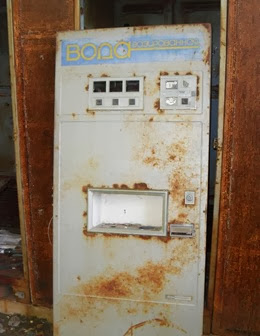

We were dropped off by the hospital where many of those injured in the initial blast were treated, and then walked through the overgrown streets to a former park with a café – unimaginatively named ‘Pripyat’ with some antique water vending machines round the back and a small harbour – half sunk below the water these days – from which pleasure cruises used to leave.

Fancy a drink… or a boating trip?

Fancy a drink… or a boating trip?

Then we continued with the leisure and recreation theme by moving on to the town’s cinema, ‘Prometheus’ which once sported a grand statue of the character from Greek mythology but which has now been moved to the front of the power station itself.

Prometheus Cinema then and now

Prometheus Cinema then and now

We then headed off the maid road, past some apartment blocks to a school where desks still lined the classrooms and propaganda posters peeled off the walls. Here more than anywhere else we’d visited looked like everyone had left all of a sudden.

Time for school…

After that we walked down the main street to the central plaza where the Hotel Polissya and the very Soviet Palace of Culture ‘Energetik’ stand whilst on the other side of the square are two tower blocks, the tallest buildings in Pripyat, one of which sports the arms of the USSR and the other the emblem of the Ukrainian SSR. Outside the hotel Matt, (the Michigan son), and I took silly photos aping the Hiroshima Shadows[3] that people had painted on the walls whilst in front of the Palace of Culture Natalie knelt down and got her Geiger counter out to demonstrate just how radioactive the moss is compared to everything else, (moss soaks up radiation apparently).

The Central Square then and now

The Central Square then and now

Hiroshima shadows at the hotel

Hiroshima shadows at the hotel

Our guide comes with glowing recommendations; she positively radiates professionalism…

Our guide comes with glowing recommendations; she positively radiates professionalism…

After the central square we wandered through the city park with Soviet propaganda posters still affixed to the lampposts before then gaping at the large Ferris Wheel which, according to Natalie, was never used as it was due to be opened the week after the explosion took place.

Propaganda in the Park, then and now

Then it was back in the van but only for a short distance to the city’s sports complex. Here Natalie was very naughty[4] and let us go into the building itself which is strictly forbidden. We crunched our way through the broken glass which covers the floor of the reception area, up the stairs, through the basketball courts and into the great expanse of the empty swimming pool. And with that rather surreal site done, our tour around the untouched USSR was completed and it was time for lunch.

All in all, my feelings were mixed. I must confess that the sheer amount of vegetation made it difficult to visualise a lot of how it had once looked and of course, ex-communist cities – of which I have visited a great many – tend to look rather dilapidated anyhow. The school in particular reminded me of the Alexander Pushkin School in Varna where I once taught where I once taught in classrooms identical to those deserted chambers, whilst the city park, the Palace of Culture and state hotel could have been in any town or city east of Vienna. This was a world which I knew intimately, yet at the same time it wasn’t, for there was no one around and nature had taken over. A feeling of disaster permeated the air, fear as the Geiger counter buzzed yet it all looked normal and harmless. The evil was invisible.

The bus took us to the power station itself and as we drove past its southern side – the direction of the prevailing wind that day – Natalie stuck the Geiger counter out of the window. In the Chernobyl 10km Exclusion Zone the background radiation seemed to be 1-2uSv/h but there it was over 8uSv/h. Even though it was hot, we kept all the windows firmly shut.

We had lunch at the canteen where the French sarcophagus workers eat. It was clean and very proletarian. As we dined I got chatting with the two beardy students. One of them had a father who was in the US Army. (which explained why, whenever Michigan mom addressed him, he replied with a very military “Yes ma’am!”), and he had lived all over the globe, (or at least, wherever the US has troops stationed which seems to be most places these days). Both of them were studying politics and specialising in secessionist groups in Central Asia and the Caucasus and so I had a good long chat with them about the ongoing conflict in Mindanao in the Philippines, (ok, not their area of interest but Military Beardy had lived there), and also about various Islamist and nationalist groups in Uzbekistan.

The two beardies were likable and intelligent guys but talking to them betrayed to me one of the essential differences in outlook between us Europeans and our Transatlantic cousins. Whilst well-read and knowledgeable their whole way of looking at things seemed to be informed by a basic starting premise that there were two sides in all these conflicts, a right side and a wrong side, good guys and bad guys. Whilst they may disagree with certain aspects of their country’s policy and direction – they were both firm Democrats and as such unimpressed by the Bush administration – they had no doubt in their minds that, in the big picture, they were the good guys and those folk who wished to secede from America’s allies were the bad guys. To me though, as a European, it never is so black and white, shades of grey abound with factors such as education, geography, interpretation of doctrine, poverty and the like bouncing around in my head and clouding the issue. To me Islamism is a pretty ridiculous political doctrine that, like most religiously-founded ideologies, can in the long run offer very little, but does that necessarily mean that a democratic Islamist regime is worse than a dictator? Maybe its something that they just need to get out of their system, like we did with our Christian fundamentalism in the Victorian Era?

Likewise with the Soviet Union, which, considering where we were, came up quite a lot in our conversations. At one point I made a comment which was somewhat positive about the old USSR and they both looked at me confused as if to say, “How on earth can you say that about the bad guys?” At the very heart of it, as we wandered around the dark heart of the old ‘Evil Empire’, I almost suspected that they were gloating, that they’d always known that the commies were the bad guys and all they were doing today was drinking in the proof of it. The communists were the bad guys, ergo they were evil, ergo they didn’t care for their own people ergo they let them all die. Simple.

But to me as I wandered around Pripyat and Chernobyl, I saw things somehow differently, somehow more mixed up and opaque, (or to use the Russian word, ‘glasnost’). Communism and those who founded it weren’t evil, it was more that as the years passed they somehow lost sight of their goals or to coin a common phrase, they couldn’t see the wood for the trees. The original impetus for the ideology had been dismay at the plight of the poor and the injustices in society. Communism was the pre-packaged medicine to right all these ills, but in their zeal to implement the cure they seemed to have forgotten about the illness. The focus shifted away from helping the poor towards the implementing of this new order and defending it against both fascism and capitalism. Chernobyl and the terrible events of 1986 is a good example of this: the great tragedy was not simply the nuclear accident, (after all, there have been plenty of these, including one at Three Mile Island in the über-capitalist USA, but more their reaction once the accident had happened. The focus was not on helping the people but more on concealing it because if it got out then the USSR would look bad in comparison with its enemies. The fault an inability to admit failure and that is not evil, but it is weak. The strong person or country admits and learns from his or her mistakes just as much as their triumphs. I just wish that some of my managers could learn from that very Soviet lesson.

Yet walking through the overgrown streets of Pripyat, I also saw much that was good about Soviet system: leisure facilities, parks, schools, kindergartens, a Palace of Culture. No, the Soviets had never completely forgotten their original purpose for existing, they did help their people in many, many ways too. There were shades of grey everywhere.

After our meal we went to the river that runs by the power station where we did something rather unexpected: we fed the fishes! Natalie pulled out some slices of bread from a bag and started throwing them off the bridge and into the water. Immediately the fish came and My God, what fish they were! Huge, mutant monsters with bulging green eyes, several feet long, churning the water as they gobbled up the white sliced! Of course, considering where we were, mutant fish or animals might be something that you’d expect to find[5] but in fact these river monsters were not mutated at all; they were naturally bulbous-eyed and had grown to such extraordinary sizes because the accident had killed off all their predators and instead these days silly tourists fed them bread. For the fish of Chernobyl at least, the explosion it seems was something of an happy event!

Chernobyl river fish, (the white spot is a slice of bread)

Chernobyl river fish, (the white spot is a slice of bread)

Our final stop was the ‘climax’ of the entire day, a trip to Reactor No. 4 itself! Although not allowed within 100m of the building, we went pretty near to that limit and Natalie’s Geiger counter buzzed merrily. We took pictures by the monument to all those who died with the sarcophagus-covered guilty mass of decomposing radioactive material in the background. You don’t get scenes like that for the family album on the Algarve now, do you? And that done, it was all back onto the bus and back to Kiev.

And after that it was all a bit disappointing. True we did stop again by the old Pripyat city sign and then in Chernobyl to view a monument to all the villages and towns abandoned due to the blast and at the border we were all made to pass through a very Star Trek-esque machine which checked if we had any radioactive material on our personages, but after that it was just one long drive through the wide open plains of Northern Ukraine which the beardies said were “a bit like Iowa” whilst learning from them and the Michigans that there was no doubt whatsoever that Obama would get re-elected for a second term six months later. Thankfully they were right, although the margin was much closer than any of them predicted.

Welcome to Pripyat!

Michigan Matt by the Lost Villages Monument in Chernobyl City and me getting decontaminated, (and I thought that stripes were meant to be slimming…)

N.B. All the photos of Pripyat in its Soviet heyday are taken from the excellent website http://pripyat.com/en.

[1] Not the actual vehicles which were too radioactive and had to be destroyed, but identical ones.

[2] Want to know how they’ll do it? Check out this brilliant video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=F9URUQvGE9g#!

[3] In Hiroshima after the A-bomb fell there are permanent shadows caused by the intensity of the nuclear blast when the bomb was dropped. Sometimes, there were shadows left of people, but no bodies found. This resulted from the extreme heat of the explosion which vaporized the bodies, leaving the shadows behind.

[4] Alas, not in that sense…

[5] Particularly if you’ve watched the 2012 cheesefest ‘The Chernobyl Diaries’ in which some stranded tourists get chased by mutants and which was filmed in Pripyat.

No comments:

Post a Comment