Greetings!

Over the past few weeks nothing has been in the news more than ISIS, IS, ISIL or whatever else they want to call them this week. To be honest, even by Middle Eastern standards, what we’re hearing is pretty horrific: beheadings, genocide of non-Muslims, forced FGM for women, women not allowed to walk the streets unveiled, mass rapes, tortures, the list goes on. Now of course, how many of these stories are corroborated remains to be seen, I suspect some, like many of those pertaining to North Korea, are made up. But then again, like North Korea, there’s more than enough there to suggest that something very, very nasty is going on.

Which brings us to the question of why: why would any regime behave like that? It’s not an easy one to answer but sadly, human beings have always veered between the nice and the nasty and in Iraq and Syria at the moment, the latter is winning. But is this problem one intrinsically of Islam as some media commentators would have us believe; is Islam fundamentally an evil religion that encourages such barbarity?

I am not a Muslim and there are many things within the faith that I seriously take issue with. Nonetheless, having travelled widely in the Muslim World and befriended many Muslims, I believe firmly that Islam is not intrinsically evil or flawed. It may not be perfect, (despite what the Prophet is reported to have said on his last sermon), but there is a lot of good there.

So, what’s happening with ISIS then? To me, of all the places that I’ve visited and read about, this most reminds me of Pol Pot’s Kampuchea (Cambodia). Think about it; a region ravaged by wars started by others, peasant fighters backed up by foreign money and arms embarking on some totally nilhistic killing spree at the behest of some ideology. Yet the Khmer Rouge were supposedly Communist and Atheist. Pol Pot however, was as close to classical Marxism as ISIS are to the Quran. Trauma can do some terrible things to people’s perceptions. Nonetheless, the example of Kampuchea is not all doom and gloom. That regime collapsed after only half a decade and the Vietnamese had literally to walk in and accept surrendering Cambodians, worn out by the misery and murder. So, perhaps ISIS will be short-lived too?

But what can prevent such terrible distortion of Islamic values in the future? The West is not the answer, but instead Muslims must look within themselves and their faith. And the happy fact is that there is a long and beautiful tradition of tolerance and spirituality there. And they could do a lot worse than head towards the place that we visit in today’s extract of ‘Incredible India’, for the Chisti Sufis are as Muslim as any ISIS brigand but as pure an example of tolerant and beautiful spirituality as can be found anywhere on the globe. Such as they are the hope that the Muslim world needs so very much…?

Keep travelling!

Fatepur Sikhri

The following day at ten my pre-arranged taxi picked me up to take me to another of Akbar's legacies: the abandoned city of Fatepur Sikhri. As I mentioned earlier, the greatest of all the Mughal emperors was also a devoted followers of the Chisti Sufis. One one occasion the Great Mughal walked forty kilometres from Agra to the village of Sikhri to consult Shaikh Salim Chisti who predicted the birth of an heir to the throne. When that prediction came true, Akbar decided to move his entire capital to the holy man's village and so constructed a brand-new city with a mosque and three palaces, one for each of his wives – one a Hindu, one a Muslim and the other a Christian. That city was an Indo-Islamic masterpiece but it was not Akbar's most inspired move. The area may have been sacred but it also suffered from water shortages and the new city was abandoned soon after its founder's death.

As it happened, the journey to Fatepur Sikhri turned out to be just as interesting as the city itself. For my driver was a chatty fellow indeed. We begun with me asking about some strange structures that I'd noticed by the roadside every so often. These were like stubby obelisks, rounded on top, and several metres high. They were obviously of great antiquity and I wondered if they had a religious purpose or perhaps marked the final resting places of notable locals, but upon asking my companion revealed that they were in fact Mughal distance markers on the old royal road, one every 2.5km. We stopped by one so that I could photograph it as brightly-painted lorries thundered by whilst the house adjacent was burning cow dung cakes as fuel, the ones waiting to be used piled up neatly against the wall.

After delving into the past we moved onto more contemporary issues. He explained to me that Tata trucks and cars – by far the most numerous on the roads – were all manufactured in Gujarat. His vehicle though was a Toyota which he declared to be “good but expensive and even more expensive to repair.”

Moving onto politics, he explained to me that the BJP is the party for “people who want India to progress” as the Congress are corrupt and they only win because “they bribe uneducated and low-caste peoples during elections”. He then went on to express the opinion that Manmohan Singh is only a “doll Prime Minister”, that Sonia Gandhi still pulls the strings and that the Gandhi family still control everything.1

I asked about the communists as an alternative as they seem to have done very well in Kerala and he agreed that they do an excellent job for in that state literacy is around 90% whereas in Uttar Pradesh, (the state in which Agra is located and also the most populous and influential state in India), it is 40%. “And the same reasons are why the road to Fatepur Sikhri is only half-finished after all this time” he declared as we bumped and rattled along said narrow and in need of repair highway.

Having breached one of the two great taboos of polite conversation, we naturally drifted onto the other for in India both religion and politics never seem to be far away. My driver, (who was a Hindu), declared that Sikhs are successful because they work hard but they don't care if they make a profit “by foul or fair”. I wondered if this was symptomatic of a low-level Hindu prejudice against Sikhs – in the train from Amritsar to Delhi the young lady whom I had talked to had declared that “their turbans make them too hot” (i.e. quick-tempered and mercurial) and if such prejudices do exist then the atrocities following the assassination of Indira Gandhi become a little more comprehensible though no less justifiable, moving onto other groups, he told me that the Jains work hard and are very moral and fair whilst the Muslims are at the bottom of the pile and the Hindus just above them. The Christians are generally rich and successful though some of their converts are low-caste converts who change their faith for money and then after one or two years move area and convert again. Such conversion he viewed as morally wrong but, surprisingly, he believed that converting for a paid education was fine. Nonetheless, the stressed that religious conversion was a career for some but then added the stern reminder that God sees all.

Switching back to his favourite subject, he then bemoaned the slow rate of progress in Rajasthan just as in Uttar Pradesh, (because Congress were in control there too). “And about Pakistan, Gandhi was wrong there, for it was good that they split for they would have held us back even more.” But what about Kashmir then? “There should be a referendum: Pakistan, India or independence? We don't want Kashmir anyway, there's nothing there but the thing is that the politicians don't want to sort it out.” I must admit that here I had some empathy, for substitute the word 'Kashmir' for 'Northern Ireland' and he could have been talking about my own country.

But what of my own country and people? “Oh, it was very good under the British! Look at how India is now and think how much better it could have been if India was still British. But with our politicians what can we do?” I asked if a solution may be in separate parties for separate religions but he did not think so despite the fact that his hated Congress draws its support from across religious and caste barriers.

I did not need to ask of course, which party my driver voted for, for he reiterated several times that the BJP was the party for educated people and then stressed that the key to progress is education. He was typical of the burgeoning Indian middle-class: he owned his taxi and had only two children – a son and a daughter with the latter doing better at school – and he did not want more.

Finally our conversation turned to the many pigs that I had seen kept in pens by roadside houses. I'd wondered that, since I'd not seen any pork on a single menu since entering India, then why on earth people kept them and what they did with them. He explained that whilst a few (low-caste) Hindus will eat pig meat, most will not as pigs eat human excrement and so the majority of the pigs are fed scraps and bred for their meat but this is sold mostly for export.

I arrived at Fatepur Sikhri a much wiser man and dined in the pre-paid restaurant which looked alright until a mouse darted across the floor in front of me. That brought fears of future vomitings, no doubt intensified by my earlier Amritsar experience but as it turned out, those fears proved to be groundless. Vermin-infested my restaurant may have been, but the food tasted fine and it was not disease-ridden enough to affect my cast-iron constitution.

Thank God.

At the café I was introduced to the man who was to be my guide. Now since I'd not asked for a guide, nor did I particularly want one then I was not overly impressed by this development, but upon reflection he did look something of a character and my lengthy chat with the driver had taught me that maybe I should try talking with the locals a bit more, so I reluctantly agreed and we piled into a tuk-tuk to get to the ancient city itself, cars not being allowed apparently.

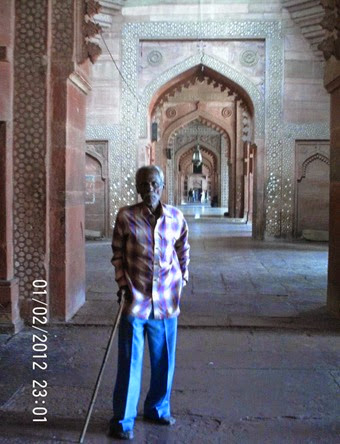

Fatepur Sikhri was impressive. The ruins extend for several kilometres but the most impressive part is where we were dropped off at the gateway to the immense Jama Masjid (Friday Mosque) in which the tomb of Shaikh Salim Chisti – Akbar's spiritual advisor – is housed. Now I've been in a few mosques in my time but this one has to rate as being up there with the best of them. A gigantic courtyard, entering through the magnificent Buband Darwaza with the Tomb of Shaikh Salim Chisti to the left of the main prayer hall whilst around the sides were elegant galleries.

Indeed, there was only one drawback to it all and that was my guide. Whilst initially interesting – he looked as old as the hills but said that he was sixty-one, although he did say that he had two wives which perhaps explained it as one aged me quite enough. No, the problem was that eccentric and quirky though he may have been, he was also extremely annoying. He said that he came from a long line of guides and from what I could gather, they had one spiel which was passed down from father to son and he had learned by rote about fifty years ago and by now the recording was so corrupted that it made little sense at all and so all I managed to garner from it was a headache.

Which wouldn't have been so bad if he'd been a recording that I could turn down, switch off or just ignore, but he was not. If I ever visibly stopped listening to his droning then he'd poke me with his finger and start all over again. Still, there was at least one advantage to having him there: whenever a tout came near he shouted at them and scared them away by waving his walking stick.

Annoying guide aside though, I enjoyed the visit. The mosque was incredible, as too were the views from the back out across the countryside. But best of all was the Shaikh's tomb. Like the dargah of Hazrat Nizamuddin, it was a rose-scented oasis of piety which even pushy guides respect. A Sufi of the Chisti Order, Salim Chisti had a reputation as a miracle worker which is why Akbar went out to his desert hermitage to ask for a son. He promptly got his wish and to this day the tomb is visited by women wanting babies.

There were lots visiting when I came, although they seemed to be more foreign tourists than pilgrims. Nonetheless, that didn't spoil it too much, although I would have loved the place to myself as I imagine it would have a similar atmosphere to Demir Baba, the Sufi shrine that I visited in Bulgaria.2 Busy or not, I sat awhile and contemplated. It was good.

And after doing that I'd seen what I wanted to see of Fatepur Sikhri. True, there were the ruins of Akbar's palace to check out where old Jodhaa had her own mini-palace next to those of his other two favourite wives, (who, strangely, were not mentioned in the film), but to tell the truth, I couldn't really be bothered, not straight after devouring the opulence of Agra Fort and not with the prospect of an annoying monologue from my stick-wielding guide to accompany it. You see, I was now beginning to realise the problem with travelling around India. The national tourist office advertises its country with the slogan 'Incredible India', obviously insinuating that India is “incredible” in terms of it being “very good”. But to me, the term should be looked at a little more carefully. Something that is “credible” is something that is “believable” and thus by adding the prefix “in-” it becomes “something that you cannot believe to be true”. And so it is with India for it is impossible to believe that one country could have so many world-class attractions. Anywhere else in the world that I've been to and Fatepur Sikhri would be the highlight of the country; there it is an afterthought to the Taj Mahal and Agra Fort. And does that equate to the “very good” meaning of “incredible”? Well, it's not bad of course, but it's not really good either for after seeing so many world-class monuments you become blasé and cease to appreciate them.

Agra

Our political and religious conversation continued all the way back to Agra before ending finally, after a couple of stops en route at the railway station this time not Agra Cantonment (where I'd arrived), but instead Agra Fort situated at the back of the spectacular fort that I'd visited the previous day.

The world has many railway stations and quite a few of them are great railway stations. Agra Fort however, is even better than that, it is spectacular, it is memorable, it is the kind of railway station that you should take a train from.

It is also British.

Opened in 1874, Agra Fort is one of the oldest railway stations in India and, apart from the fact that an ancient bazaar was levelled to make way for it, it represents everything that was good about the Raj.

If Fatepur Sikhri showed you what was good about the Mughals; a blend of Persian with local architectural styles, then Agra Fort Railway Station is the same with the British, the terminal buildings having a hint of Huddersfield and a dash of Delhi. But it's inside under the overall roof, (all the best stations have one), that the real triumph becomes apparent. The place is busy, well-used, useful by all stratum of Indian society. Yes, the Mughals may have built great tombs, forts and palaces, but what impact did they have on the life of the common man beyond creating an extra tax burden? Ok, so I'm not so naïve as to believe that the British were just being nice when they built railways across the length and breadth of India, of course their main goal was to make money, but they did have what they believed to be a civilising mission as well, “the White Man's Burden” they termed it, racist perhaps today but well-intentioned back then and this was the result.

But Matt, I hear you say, that goes for all railway stations! What makes this one so special? Well, as the train pulls out of the beautiful Victorian terminal and you rest your eyes on the magnificent Jama Mosque and Agra Fort next-door, well, then that is what train travel is all about!

Not that the rest of the journey was as spectacular as that. The outskirts of Agra were the same slums I'd viewed around Delhi – piles of rubbish, lads playing cricket on a concrete yard, jerry-built housing and marauding cows – but soon the city was gone and the Shatabdi Express was powering through the Uttar Pradesh countryside, as perfectly flat and lush as all that I'd seen so far in India and, alas, also as dull. I tried a conversation with the couple opposite but they apologised and said that they didn't speak English. I would have believed them too if only he were not reading an English-language newspaper! Whatever, I retreated to my books and finished Paulo Coelho's mediocre offering 'Aleph' which I'd started on the Delhi-Agra train from Hell.

But as we passed from Uttar Pradesh and into Rajasthan, the landscape slowly began to change, becoming more arid and then, shock horror, the first hills of the trip loomed. Barely hillocks I admit, but nonetheless, something at last to divert the eye. As we drifted through the towns and villages, I therefore did keep one eye on the passing landscape whilst the other I turned to a different activity: a short story that I had had in the back of my mind for years. Was a railway ramble through Rajasthan just what was needed to prize it out and give it life?3

1BJP = Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian Peoples' Party). Formed in 1980 this is a Hindu nationalist party that has formed several coalition governments. In 2014 just over a year after my trip, they achieved a majority in the Indian parliament and formed a government. Congress = Indian National Congress. The oldest party in India, it was the force that fought for independence from Britain and included such luminaries as Gandhi and Nehru in its ranks. Traditionally the most powerful and influential party in India, it has gained a reputation for cronyism and corruption. When I visited the Prime Minister was the Congress' Manmohan Singh (a Sikh) but Sonia Gandhi, the widow of Rajiv Gandhi, Indira's son, was seen as the real power behind the throne.

2 See my travelogue 'Balkania'.

3 The short answer is, no. Over a year on and it still sits there half-written.

Technorati Tags: uncle travelling matt,matt pointon,travel,blog,incredible india,india,agra,fatepur sikri,jodhaa,akbar,chisti,sufi,shaikh salim chisti,unesco,bjp,congress,bharatiya janata party,caste,uttar pradesh,corruption,shatabdi express,mughal gurdwara,milepost,dung,religion,hinduism,islam,muslim,christian,jain,sikhism,tuk-tuk,rats

No comments:

Post a Comment